From the Archives: MOBY | THE GOD FACTOR INTERVIEW

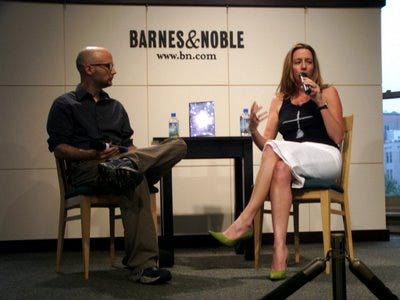

From our live event at the Barnes & Noble Union Square, NYC on June 29, 2006

Long promised, and well overdue, here is the transcript of my live "God Factor" interview with Moby, June 29, 2006 at the Union Square Barnes & Noble in NYC.

My thanks to Moby for his gracious participation and candor. Hope you find it as intriguing as I did.

MOBY: Um, before we start talking, I have a question: How come I’m not in the book?

CATHLEEN: You …