A Year On: Remembering Lin Brehmer, Our Best Friend In The Whole World

On the one-year anniversary of his death, while I'm working on a project about confronting fear and embracing joy, I thought I'd share again some thoughts from the day Lin left this world.

How has it been a year?

Not a day goes by that I don’t hear his voice in my mind cheerfully insisting, “It’s great to be alive.” Lin embodied those words and they are part of his joyous legacy. May we remember him always, take a few minutes today to listen to John Fahey’s ‘Sunflower River Blues’ and then spin whatever music moves our souls.

Maybe dance like we don’t care who’s watching (because why should we?) in the living room, at the office, on the el, wherever we find ourselves.

Tell someone you love that you love them. Make them laugh or make ‘em a sandwich. And give thanks for our best friend in the whole world whose light continues to show us the way….

If you’d like to make a contribution in Lin’s memory to two organizations that were important to him — Intonation, which helps Chicago youth experience and make music on their own terms; and Nourishing Hope (formerly the Lakeview Pantry), which provides food, mental wellness counseling, and other social services to neighbors in Chicago — you can do so by clicking on the buttons below.

Originally posted on January 22, 2023

My friend Lin died today.

Five words I hoped I’d never have to contemplate, nevermind type.

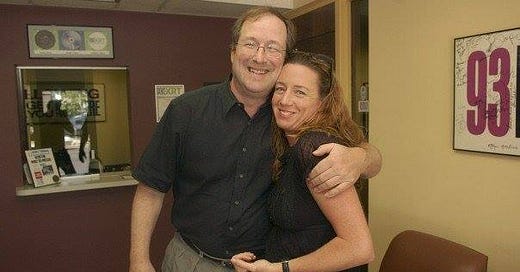

Lin Brehmer, a musical icon in Chicago where he was the morning drive host on WXRT radio for nearly 30 years, the first voice I heard in the morning from my junior year of college until we moved to California in 2009, one of the most truly wonderful human beings I’ve ever had the pleasure of knowing (and being known by) professionally and personally, left us just before the sun rose over Lake Michigan this morning. The two greatest loves of his life — his spouse (and sweetheart since their college days at Colgate) Sara and son Wilson — were at his side.

Lin had been battling prostate cancer since last year and as his longtime colleague and friend, beloved Terri Hemmert, announced on air, “We must inform you that we all lost our best friend. Lin Brehmer fought cancer as long as he could. He passed early this morning, peacefully.”

Lin was one of Terri’s best friends. Lin was one of my most precious friends.

Lin made everyone he met, whether in person or via the airways, feel as if he was their best friend.

When I say Chicago is in mourning for Lin, it is not an overstatement.

And rightfully so. Lin is and was ever the best of Chicago, the embodiment of the city’s big shoulders and even bigger hearts. He was the opposite of pretentious. Just a regular guy (even if it was a different WXRT DJ who voiced that enduring on-air character.) He was as deep as he was accessible, qualities that came across in his always outstanding on-air essays, Lin’s Bin. (I hope the radio station makes the entirety of his surely hundreds of Lin’s Bins available to us now that he’s gone.) You can find a selection of them from recent years HERE.

But please pay close attention to his Bin from last November called “How Are You Doing?” when he briefly returned to the airways after Thanksgiving between rounds of chemotherapy. Just make sure you have some tissues on hand.

I cannot fathom never seeing Lin again, meeting him for lunch, running into him at an event, spotting him in the wings of a show at Metro or the Riv, standing inconspicuously at the back of Schubas while a singer-songwriter worked her magic on the small stage. I am so grateful for the symmetry of grace that brought us together for the last time. U2 were in town and so was I. Lin was running to the bar at the United Center moments before Bono, Larry, Adam, and the Edge walked out on stage. We hugged, I was working the show so turned down his offer to join him in a whisky, we wished each other a “good show,” and I know I said “I love you, man.” I’m so glad I did. And I so wish I had joined him in that whisky.

I was a fan of Lin’s — and honestly, I can’t imagine anyone who encountered Lin not becoming a fan on his — for at least a decade before we met through the media creatures culture of Chicago. If memory serves, it was at an oyster fest in Grant Park in autumn. There were mollusks and I’m pretty sure there was whisky, too, but I’m positive there was laughter.

Lin’s warm smile preceded him wherever he went. He was full of mirth and a lust for life that was as contagious as it was unquenchable. He was also one of the most eloquent writers I’ve ever known. He loved food and music of all kinds and people of all kinds and fun of the best kind. He loved the Cubs and golf and Ireland and literature and mischief and hugs and sandwiches.

He was a such a fan — of life. Of me. Probably of you, too.

When my son Vasco first arrived in Chicago from Malawi for lifesaving open-heart surgery in the spring of 2009, one of our first outings was to visit “Uncle Lin” in the WXRT studios downtown. While were there, he asked if Vasco would like to record an “air check” in the fashion of Lin’s legendary tagline (and lifeway):

“It’s great to be alive.”

Here it is:

Lin made an indelible impression on our Wee Man, as we called him at the time. When we learned last summer that he was taking a leave of absence from XRT to undergo treatment, not-so-wee-anymore Vasco and I, who were on our way to Big Sur, sent “everyone’s best friend in the whole world” a video message:

It broke my heart to tell Vas that Lin had died. We adored Lin. He adored us. He made sure we knew it. We did. And I bet, if you were lucky enough to know him even a little, you felt at least a little bit adored.

A few years ago, when we had a rough patch here in California, he sent me a message that said, “Just come home.” It moved me to tears then and cued a sobbing jag today. I’ve never wanted to beam myself to Chicago, to “just come home” more than I have today, to be with our friends and the city that he loved and that loved him back.

I wish I had seen Lin one more time. I’ll never not wish that. The last time I heard from him he was checking up on me in the hospital even as he was fighting his own mighty battle back home in Chicago. He made me laugh. He always made me laugh.

Nearly 17 years ago (how on earth has it been that long???), Lin and I began a public conversation about spirituality and music. It started as an interview for the Chicago Sun-Times, where I was the religion columnist at the time that ran with the headline “The Rev. of 'N' Roll: DJ in tune with the lyrics, rhythm of faith, and two years later, it became a chapter called “Driving and Crying” in my 2008 book about grace, Sin Boldly.

Here it is:

DRIVING AND CRYING

After being in the newsroom around the clock for a couple of days after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, I came home exhausted and broken — spiritually, emotionally, mentally. I collapsed on the futon and turned on the TV just as U2 began to play live from London during the international 9/11 telethon.

And if the darkness is to keep us apart

And if the daylight feels like it’s a long way off And if your glass heart should crack

And for a second you turn back

Oh no, be strong

Walk on, walk on

It was precisely what I needed to hear. Not from a rock band, not from any other human being. It’s what I needed to hear the Creator of the Universe say.

That moment of grace in the guise of a song reminds me of something I once heard the author Frederick Buechner say: “Pay attention to the things that bring a tear to your eye or a lump in your throat because they are signs that the holy is drawing near.”

One perfect summer night a few years ago, the holy, as it does, snuck up on me in the most random of places. A peachy gloaming lit the western skyline as I drove home, top down on my ancient Miata, through the quiet rough-and-tumble streets of Chicago’s west side. Blaring from the tinny speakers I’d cranked up to almost 11 was one of those songs that makes me sing at the top of my voice (even in a convertible) and throw my hands in the air — “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” by the Rolling Stones.

Driving while listening to music is one of life’s great pleasures. It’s a spiritual practice I learned from my father. When I was a little girl and he was working on his doctorate at Columbia University in New York City, sometimes I would accompany Daddy on the ride from our home in Connecticut into Manhattan. Many of my fondest memories from early childhood are of those regular road trips in his Karmann Ghia, whizzing along the Henry Hudson Parkway, listening to his favorite traditional jazz station on the AM-only radio, talking about nothing in particular, and eating Cracker Jacks from the box he always kept in a hidden compartment behind the cushions of the backseat.

Years later, when I got my driver’s license, I would spend hours driving back roads, singing along to cassette tapes of my favorite bands or the alternative radio station out of Long Island that I could tune into in the car but not in my bedroom at home.

I do my best thinking in the car, taking the scenic route and the long way home to stretch even a quick run to the supermarket into a contemplative journey, alone with my thoughts and some righteous tunes. There’s something about the insulated solitude of a car that gives me permission to sing with abandon while working on various existential conundrums.

As I rolled up to a stoplight near the United Center (home of the Chicago Bulls and Blackhawks) that summer night, the Stones song ended and a familiar voice took to the airways, hitting me upside the head with some unexpected spiritual wisdom, leaving me gobsmacked (or, more accurately, God-smacked). It was Lin Brehmer, the radio station’s most popular disc jockey, reading one of his “Lin’s Bin” essays, this one an answer to some listener mail — a letter from a fellow in Indiana who asked, “I’m not getting any younger. Should I start going to church? If so, which one?”

The DJ’s answer, in part, was this:

As we get older, we begin to consider our mortality. The godless man might ask himself at the end of his life, “Have I miscalculated? Should I have communed with my maker?” Even W.C. Fields, a man known more for his hatred of kids than his love of religion, was discovered late in life with a Bible on his hospital bed. “Bill,” a friend, asked, “what are you doing reading the Bible?” and Fields replied, “Looking for loopholes.” . . .

Finding your faith later in life brings a different perspective to religion. Still, watching a child you know grow up and solemnify their belief in front of family and friends will move you in mysterious ways. Is this the same baby in a stroller now chanting in Hebrew? A sweet three-year-old girl I know was once at Mass, and as the bewildering experience wore on, she became impatient and began to squirm. Her mother tried to placate her by pointing out a picture of the Christ child. In a voice that reverberated to every chamber of the stone cathedral, the innocent shouted, “I HATE THE BABY JESUS!”

Now, here comes the part that got to me, taking me by surprise and bringing tears to my eyes. “Before you wonder at the consequences,” Lin said, “remember what Jesus himself said: ‘Suffer the little children, and forbid them not to come unto me,’ because I can take it.”

Whoa. That’s about as profound a religious statement as I’ve ever heard. And it’s not exactly what you might expect to hear between rock anthems on Chicago’s premiere rock ’n’ roll radio station. But WXRT is not your average radio station and Lin Brehmer is not your average disc jockey. He is known, in fact, as “The Reverend of Rock ’n’ Roll.” It’s a moniker Lin earned in the early 1970s when he was a young DJ in Albany, New York, where he hosted a show on Sunday mornings. It’s a nickname fellow jocks bestowed on him because of his proclivity for reading from “Book Nine” of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, particularly the line that says, “Shall that be shut to Man, which to the Beast is open?”

“OK, mister, I think it’s time you and I had a chat about this ‘Godstuff,’ ” I told “the Rev.” in an email after I heard him read the essay titled “Choosing Faith,” the one that had moved me so deeply. Never one to flee from a dare, Lin gamely acquiesced to a thorough grilling in his office at the radio station, and, as is often the case when I go looking for God in the places some people would say God isn’t supposed to be, what I discovered was much more intriguing than I could have imagined.

I have a favorite T-shirt that reads, “Jesus is my mixtape.” When I bought it, I thought its slogan was charmingly quirky, but over time it has acquired this transcendent quality, a motto that sums up my belief that everything — everything — is spiritual. At the center of that everythingness, as a pastor friend of mine likes to describe it, is a universal rhythm, a song we all play, like a giant, motley orchestra. Sometimes in tune, sometimes off-key. We call it by different names. Still, it remains — if only we have ears to hear it — the eternal soundtrack that plays in the background of our lives.

“I’m a mystical expressionist,” he says. “I take the idea of mysticism very seriously, but I sort of paint it my own way. I think the idea that there is something within each and every one of us that can take us to a place we’ve never been before is what makes it great to be alive.”

— Lin Brehmer

For the nearly twenty years that I’ve called Chicago home, WXRT has provided the (literal) soundtrack to my life. It was the first radio station I tuned to when I arrived in Illinois in the fall of 1988 to start my freshman year at Wheaton College, and it’s still the station I’m tuned to while driving or cooking in the kitchen or just puttering around the house. Since 1991, except for the days when I oversleep, Lin has been the morning mixtape master, spinning the music that starts my day. In 2002, Lin began reading on the air his thrice-weekly “Lin’s Bin” essays, running the gamut from the silly (“The Hokey Pokey: Is That What It’s All About?” for instance) to the blatantly spiritual.

The morning I turned up at the radio station to grill Lin about God, he had just finished his morning broadcast and was reaching for an ancient, bedraggled copy of Norton’s Anthology of English Literature (in two pieces with no cover) as I walked through the door of his office. “I’ve always been fascinated by religion and man’s relation to the divine,” Lin told me flipping pages in the book to find Paradise Lost so he could read from his favorite passage.

“I’m a mystical expressionist,” he says. “I take the idea of mysticism very seriously, but I sort of paint it my own way. I think the idea that there is something within each and every one of us that can take us to a place we’ve never been before is what makes it great to be alive.”

Music is a vehicle that propels Lin — and me and so many other people — toward a place we might call Grace. Music is part of our cultural conversation, and in nervous times such as these, it has a lot to say. The idea that music has the power to move people in a way nothing else does seems never to be far from Lin’s mind. “People ask me why I got into radio,” he says, “and for me, it was almost always a musical thing, almost as if I wanted to preach by playing songs that said something.”

The musicians that shaped his consciousness as a teenager — Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, the Beatles — were more than just drug-addled rock stars. They were prophets, Lin says, warning us about the future, just like Jeremiah and Ezekiel did in the Hebrew Scriptures.

Modern musical prophecy didn’t end when the Summer of Love drew to a close in 1968. Lin keeps on his desk at the radio station a framed picture of his teenage son, Wilson, playing a blue Fender Stratocaster guitar. It reminds him that music has the same effect on Wilson and his peers that it did on his father as a teenager.

“I absolutely think that teenagers or young people are as much affected emotionally and spiritually by the music they hear as by any sermon they hear in a church,” he told me without a hint of bitterness or sarcasm in his voice. “Part of the reason I have trouble going to church and staying in church is feeling like the sermon some minister is espousing wasn’t connecting with me in any way, whereas a good four lines from a John Hiatt song could mean so much more to me.”

As someone who had her first spiritual epiphany at the age of twelve while listening to U2’s “Gloria” for the first time after school in a friend’s living room, I can attest to this. The message can even be the same — sometimes, as was the case with “Gloria,” the words themselves are the same — as what we hear in church or temple, mosque or shul. But there’s something mightily powerful about hearing the words sung aloud with passion or pathos, as a guitar wails and a bass line thumps.

“You talk about what your religious faith is supposed to do for you and what a minister or a rabbi is supposed to do for you, providing you with counsel and wisdom and sustenance and support — sometimes the quickest avenue to all of those things is a song that you love.”

— Lin Brehmer

What brings a tear to the eye of one person is not the same thing that puts a lump in the throat of another, but for everyone there is some music that changes their life. Whether it’s some pop cutie-pie on American Idol warbling a song written by committee or Tom Waits grunting through “Swordfishtrombones,” there is some music that gets inside of everyone. For Lin, it’s music like “Good Day for the Blues” by Storyville, “Gimme Shelter” by the Rolling Stones, or Bob Dylan’s “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).”

For me, it might be Jeff Buckley’s “Hallelujah,” “Not While I’m Around” from the Stephen Sondheim musical Sweeney Todd, or “Nessun Dorma” from Puccini’s opera Turandot. (The rousing, climactic verse, “Tramontate, stelle! All’alba vincerò! Vincerò! Vincerò!” reduces me to a puddle every time I hear it. )

“You talk about what your religious faith is supposed to do for you and what a minister or a rabbi is supposed to do for you, providing you with counsel and wisdom and sustenance and support — sometimes the quickest avenue to all of those things is a song that you love,” Lin says. This reminds him of music he also associates with 9/11.

“The day after September 11, I opened my show with a song I never play just as a song. Now it’s the first song I play on the anniversary of 9/11 every year. It’s called ‘Sunflower River Blues’ by John Fahey. It’s a very simple acoustic guitar instrumental. But for me,” he says, leaning forward in his chair, his voice dropping, “it has that same feel as the second movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony.”

“Dunnnn dun dun dun, dunnn dunn, dunn dun dah dunn — it kind of plods along, but there’s a kind of resolution in the musical phrasing, and it’s the same thing in that John Fahey song. It’s got a certain melancholy feel to it, but at the end it kind of resolves itself in a major chord that makes you think everything’s gonna be OK,” he said, smiling wistfully. “It’s gonna be alright.”

That day at the radio station, as Lin expounded on music’s more mystical qualities, I became aware of a song playing quietly on the radio receiver on his desk tuned to WXRT. It was U2’s “Walk On.”

When I mentioned it to Lin, he turned up the volume, and we were both struck still, as if an unexpected third party had just joined us.

Nearly a decade after our first conversation about the mystical power of music, Lin and beloved Terri, the godmother of Chicago radio, who for years followed Lin’s morning drive show as the midday host on XRT, joined me for lunch at a favorite haunt where we discussed all things musical and spiritual. I’ve posted it in the archives here on the site and if I can scare up the audio version later, I will post it as well. The link follows, but this is one of my favorite bits of Lin-ness from that precious confab.

“I don’t know if these experiences are strictly spiritual or religious or if they’re just overwhelming emotionally or if there’s really much of a difference between religious and overwhelming emotionally, but when my two brothers and I get together at least once a year — they’re all very bad musicians; I play guitar, my brother David plays banjo, and my brother John plays mandolin — and my son Wilson is a very good guitar player. Really the only time we play our instruments to any great extent is at our family reunion and because we’re such bad musicians the only kind of music we can play is old-timey folk songs. And one of the things my father loved beyond all measure when he was still alive was to have all three of his sons and his grandson singing Woody Guthrie songs and singing songs from the songbook of O Brother Where Art Thou? We’d sing ‘one fine morning when this life is over, I’ll fly away,’ and with my son, who is actually musical, we’d get a two- or three-part harmony going and it was really, for a bunch of amateur brothers getting together, it was really beautiful. And my father would say, ‘Boys, no matter what else happens, when I die, I want you to promise me that you’re gonna get together and sing this song for me.’ So when my father died, we had a little service for him … in the retirement home’s little auditorium with a stage. My dad was a very affable guy, everybody in the community knew him. So it was a packed house in this little auditorium of these old people and some of the family that we had that flew in, and my two brothers and my son on stage singing, ‘I’ll fly away, O Lordy, I’ll fly away…’”

Lin also told us that summer afternoon in 2015:

“I have explained to people that whatever else happens at my funeral — and I hope there’s a lot of whisky and a lot of beer — but at some point the John Fahey song ‘Sunflower River Blues’ must be played because of all the acoustic, instrument music I’ve heard, that song — it’s almost got an Indian Hindu drone — that song completely takes over my mind….

“To my mind, it’s very much like the Second Movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony,” Lin said. “That has a progression that sounds like a man trudging to the end of his life. Aaaaa aa aa aaaaa … What happens at the end is that the song resolves itself musically baaaa bump bump baaa bump… so there you are, you have this struggle, but at the end of the song it slides you back up again. It’s kind of the same thing with that John Fahey song.”

Lin L I V E D . He was fond of reminding us to take nothing for granted because it’s simply great to be alive.

I’m so grateful for Lin’s having been alive. I want to honor him by living my life, every moment, even the shittiest ones, to the fullest.

I love you, Lin. Thank you for every single thing.

Be brave and kind, my friends.

Please don’t forget that you haven’t met yet everyone you will love and you haven’t met yet everyone who will love you.

And in the immortal words of the late, great Warren Zevon: Enjoy every sandwich.

Thank you for this piece. I’ve been missing listening to Lin lately and have been thinking about all the music he introduced me to with a phrase like, “the best song ever written” or “the best song in the whole world.” And it was always a different song. Some I knew; some I didn’t. And he was always right. It was the best song. And he was the best morning friend I ever had.

I miss your Sun Times column and was so happy to find you here on Substack. I find your writing thought-provoking and often very moving. Today is no exception. Thanks for sharing your gifts with me.