Smidiríní: Wild Fuchsia and the Holy Well

Stories, images, and impressions that make up the mosaic of experience here in Ireland: Today, an evening ramble wherein I lose my way and find the numinous—an ongoing theme in my life, I realize.

Yesterday late afternoon, having spent much of the day icing my lower back (it continues to give me fits, this time after some [apparently] too-rigorous grocery shopping the day before), I had to get out of the house and move my body, even if it was just for a gentle wander on foot.

Hiking and rambling trails criss-cross this part of northwestern Mayo, marked by signs that look like a shepherd leaning on a crook with a lamb on his back but in fact are meant to be a hiker carrying a long walking stick. There’s one such sign and trail just off the high street of the town nearest to the house where we are staying presently, so I carefully pulled on hiking boots, lumbar brace, and foul-weather gear—a local character named Tommy had informed us, when he stopped by on his tractor to chat a few days earlier, that Thursday was going to be a wet one (local wisdom we had confirmed with professional meteorologists).

It turned out to be more of a “fine, soft day” than anything more gale-ic (sorry, not sorry), but the weather along the Wild Atlantic Way often changes on a dime, so my inner Girl Scout tossed a rain poncho in the back seat of the car before heading out to find the trailhead in town. When I got there, despite driving up and down the roads where the signs were pointing, I couldn’t find it. And when I googled, I realized the trail is marked “difficult,” and “difficult” is not something I should be putting my sore back through.

So, I searched a bit more, settling on a trail that was farther away than I wanted to drive, but about the same length of time I often drove in California to reach my preferred trails.

About 10 minutes into the drive toward Ballina, I noticed one of those hiking shepherd signs and made a sharp left toward the ocean.

I’m so glad I did.

Just past Bessie’s Bar and before the entrance to Kilcummin Harbor, there was a turnout with a large map where I parked my car and got out to take in the gorgeous vista as summer sun glimmered off of the waters of Killala Bay. According to the map, there were three possible routes, all loops of various sizes, to choose from and I chose the green path, as it was the shortest and I’m still trying to take it easy and be kind to my back.

As soon as I began to walk north along the road, I saw some ruins in a field on the bayside. There are countless ruins in countless fields throughout rural Ireland, particularly in the West, so this was not unusual. But because I was on foot, traveling even more slowly than when I’m trying to shift from first to second gear in our new-to-us Jeep with manual transmission going into a curve on a narrow country road, I looked at it long enough to realize it was a church—or at least it had been.

I walked toward the site, not sure if it was public or not, but seeing no gate or other markings meant to keep trespassers out, I cracked on toward the ruins surrounded by a few headstones indicating a cemetery or burial ground. When I stopped to take a few pictures, I also asked my pocket robot to tell me more about what I was looking at, and learned that the church was more than a thousand years old.

Goodness. That’s old. I’ve never lived in a place with structures still standing after a few centuries, nevermind millennia. As an American, I’ve lived on land that had been inhabited by indigenous peoples for many thousands of years before colonizers stole it, drove them off of it, and/or did their best to wipe them out in the process. In Ireland, what I’ve just described is a familiar experience.

There’s recorded history and then there’s history, centuries and millennia of human experience that wasn’t written down in a book or memorialized in stone, wood, and metal; or that was systematically destroyed by oppressors.

As I was trying to fathom the ancient humans who had walked this land thousands of years before me, I noticed something else: a low set of stone stairs leading down to another site with a smaller building that, from a distance, looked a bit like an old stone dog house.

A faded sign quickly informed me that it was in fact a holy well, one belonging to a saint I’d never heard of (many of them in these parts as well, of course) and who some believe is buried in the ancient church yard a few hundred meters south: St. Cuimín.

Like many Irish forerunners who are considered saints, either officially (i.e., as recognized by an ecclesiastical body) or popularly (by the people who lived and still live here), Cuimín’s story is part history and part “myth.” At least that’s the consensus of what the reading I’ve done about him in the last day has said.

One source referred to him as a “folk saint,” who likely lived on Iona during the 7th century, not long after St. Columba arrived from Ireland to the small island in the Scottish Hebrides in 563 to establish a monastic community there that may have been where the Book of Kells project began and which certainly is considered one of the birthplaces of Celtic Christianity.

A popular tale about Cuimín says he was “high born” to a noble family, perhaps even to one of the fabled kings of Connacht. Another says, not unlike Moses, he was “shipwrecked” as an infant along the shores of Killala Bay and discovered by a local family after their cow kept vociferously licking the boat until they found the baby inside the wreckage. They took Cuimín in and reared him as their own, and he was pious and wise as a boy and a man.

Whatever the actual story (and there are many more), Cuimín has been an important figure culturally and spiritually in this part of Mayo. For many centuries, people locally have believed that the mud from his resting place near the church ruins—and later the water in a well steps from where a leacht (a mound of stones larger than a typical cairn) marks his grave—possessed curative properties.

When I approached the small, stone edifice that houses the well, it was clear the place was very much still in use. There were plastic rosary beads hanging near the entrance, a modern statue of the Infant Jesus of Prague inside adjacent to a plasticine statue of the Virgin Mary in a grotto to the infant’s right. Moreover, the ground where a visitor would crouch or kneel to reach the water inside (there was a metal chalice tucked into an alcove that seemed to say, “I’m here if you need me” as I ducked my head to enter the sacred space) was muddy.

Perhaps I hadn’t been the only visitor that day.

I don’t know what I believe about “healing waters” and the like, but my back hurts and I’d be lying if I said I didn’t stretch to dip my fingers in the water, make the sign of the cross, place them briefly on my lower lumbar area, and offer a silent prayer for physical restoration.

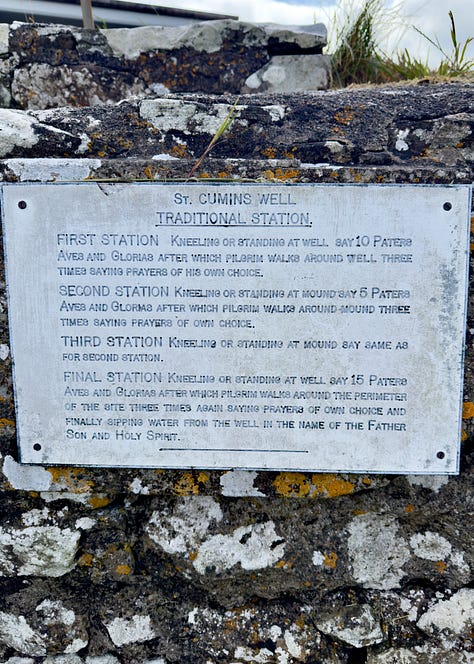

When I got up off my knees, I noticed a sign fastened to an old stone wall a few feet away with instructions for pilgrims who had come to visit the holy well. (It’s pictured below in the photo gallery.) Of course I’d not read the instructions. I didn’t read the instructions closely when I set up my new Irish mobile phone last week either, which is why it couldn’t receive texts until yesterday. But I digress…

Even when I read the instructions, I’m still not much of a rule follower, at least not now in what Anne Lamott called the “second third of life.” This also feels like a cultural predilection I might share with my new neighbors here in Ireland. Rules and instructions are more … suggestions than something to be taken or followed literally or to the letter.

Still, it was a place thousands of people before me had come with some kind of faith hoping for some sort of encounter with transcendence, and I’m game for such things, so I read the suggestions for how to move through the “stations” of the holy well.

I got the part about starting on my knees and praying while I circumambulated the well itself and the two mounds/cairns/leachts that sit more or less side-by-side in front of the well’s entrance. So, I walked around each “station” three times while silently reciting, “Be still and know that I am God” to myself. It’s a prayer or mantra I return to often when I’m anxious about something, especially things that feel beyond my control.

There were countless moving parts that had to work to get us to Ireland and there are countless more that will have to align if we are to stay in this place where we’ve long dreamt of dwelling. It’s complicated and the future is uncertain. And life is generally pretty complicated and the future is always uncertain, so … “Be still and know that I am God” is an evergreen for me, for many of us.

When I finished my circumambulations (I didn’t notice the fourth instruction to go around the entire grounds three times at the end until I was looking at the image in iPhoto today—oops!), I quickly realized that the shaped I’d made—the path I’d literally trod—was that of a triskelion. Sometimes also known in Irish as a triskele, the three interconnected spirals are an ancient symbol important to Celtic spirituality but by no means exclusive to it.

The triskelion has many meanings in many cultures—the Holy Trinity, phases of life (maiden, mother, crone), three earth elements (air, water, soil), mind-body-spirit, infinity and connection, etc.

What resonates most meaningfully for me is how the triskelion is a reminder that our progress through this world is an ongoing, continuously unfolding process, an evolution that doesn’t follow a straight path.

It’s circuitous and continuous, a journey made of a single, uninterrupted, interconnected through-line even when it might feel as if we’re doubling back and just walking in circles.

Well, I wasn’t expecting that moment of clarity when I left the house to get in a little exercise between rain showers. But it shouldn’t have surprised me. I often say I walk or hike “to clear my head.”

Yesterday, I was anxious and in pain. I needed to move and get some fresh air (it’s blessedly plentiful here), to change my perspective and breathe deeply.

I walked on from Cuimín’s ruins and (hopefully) healing waters, following the green route as it turned inland away from the waterfront. Soon I found myself enveloped by the flora and fauna, smells and sensations of a rural backroad, walking past working small-holder farms, middle-class family homes, and the more recent ruins of stone homes from the last century.

Mayo is in Connacht—one of the four provinces in the West—a place that often has been called “inhospitable.” It’s rocky and windswept, mountainous and stormy. The land is terribly difficult to farm and throughout its history, ancient and contemporary, it’s been hard to make a living in these parts. There’s been a lot of misery here and also heaps of resilience.

Whatever it is about Connacht, it has drawn me back, time and again, since I first spent time here more than 30 summers ago. It’s tough and it’s beautiful. My impression from past visits and our stay this last fortnight, is that its people are, too.

As I continued my walk, I began paying closer attention to birdsong and the plant life along the route. And not for the first time, I marveled at how fuchsia grows wild in Ireland.

Fuchsia always has been one of my favourite flowers. My mother, who had a lifelong green thumb, perhaps inherited from her father who was renown for his rose garden, also loved them and each summer in Connecticut, she would plant hanging baskets full of them and dote on them, trying to coax them through an entire season, usually without resounding success.

I have killed more fuchsia plants than I care to count. Southern California (where seemingly everything grows) was too hot and too sunny for fuchsia’s delicate American varieties. They would fry in the sun inside of a week. Elsewhere, even if I managed to get the mix of sun and shade and temperature right, if I forgot to water them once, that was it. They wilted and never came back to their fully glory.

Here, though, particularly in the West of Ireland, fuchsia thrives, growing wild as hedgerows sometimes as tall as three meters.

Only after making a mental note to look up why fuchsia goes gangbusters in this island in the North Atlantic and in its wildest, most “inhospitable” terrain better than anywhere else, did I learn that the plant is not native to Ireland.

The species hails from Central America and the Caribbean, only arriving on Ireland’s shores in the 1820s.

Michael Viney, the late, legendary columnist for the Irish Times, who lived in Mayo and often chronicled his life in the West, wrote:

‘If the Wild Atlantic Way ever needed a floral emblem, it would have to be the fuchsia: its vivid and elegant flowers decorate wayside hedges from Donegal to Cork. Autumn finds them still abundant, waiting on the first good gale to carpet high-hedged coastal roads with drifts of scarlet and purple.

‘An early French botanical monk, Charles Plumier, hunting new plants for Louis XIV, found this one in Hispaniola and named it in honour of a German botanist, Leonhard Fuchs, pronounced “fooks”. The name has been safely mangled on Anglo tongues, once producing “back to the fuchsia” as my favourite punning headline to this column.

‘From more than 100 species of fuchsia, the full and formal name for the cultivar that thrives in western Ireland is Fuchsia magellanica Riccartonii, blending origins in southern Chile with hybridisation in Scotland. Arriving in these islands around 1823, its rapid growth on frost-free land saw it flourish both in big house shrubbery and sheltering hedgerows on western farms.

‘Its easy growth from raw twigs rivals even that of the willow. My first planting of cabbage seedlings in the windswept earth of the acre was sheltered by little branches of fuchsia snapped off a handy hedge. Simply pushed into the ground, these quickly took root and grew to weave the first of a dozen windbreak hedges, dividing our bare quadrant of hillside for vegetables and hens.’

Fuchsia might be difficult and fragile in some settings, even those that would seem conducive to cultivating its distinctive colorful, parasol-like (another writer described them as ballerinas with uneven legs) blossoms. But in the right place, even if it doesn’t seem like the obvious or natural choice, it’s as hearty and nearly indestructible as it is beautiful.

There’s a metaphor and a lesson in there that I’ll be unpacking as our sojourn in this wild and wondrous place continues.

I’ll be back next week with the first in a series about learning to slooooooowwwwww dooooowwwwwnnnnn and how the Wild Atlantic Way is teaching me to do it.

P.S. Smidiríní is a nifty Irish word (basically meaning “pieces”) from whence the English word “smithereens” is derived, apparently. The smidiríní are the bits that are left when something is “blown to smithereens” but they also are the fragments, large or small, from which stunning mosaics are made.

Please be as brave and as kind as you can.

And remember that you haven’t met yet everyone you will love and you haven’t met yet everyone who will love you.

Love from me,

Funny you mention the fuchsia. I just said to Henry the other day that I noticed more of it this year in Ireland than before. Maybe it's a bumper crop! Of course, there's the rhododendron everywhere too in Ireland, also not native, but pretty and prolific enough to be called "the beautiful killer" by horticulturalists for its crowding out other species. Reading something about a plant in Ireland not long ago--gorse, maybe?--the author used the word "nativized" to indicate something not of the place but having adapted to it to the point it also can no longer be considered not of the place. So it's both foreign AND domestic. Reading that, I couldn't help but reflect on my experience as a former ex-pat, and the uniqueness of occupying that space, as you're now doing, with feet, sensibility and soul forged in various worlds. I'll be curious to hear how that shows up for you as your adventure continues.

thank you for your stories.