Sunday Stories: Skylights and Healing Waters

What happens when we look for miracles or mercy? Whether a paralyzed man lowered through the roof by his friends or the millions who flock to Lourdes, whatever "it" is occurs with and in community.

When I was 12 years old, my family moved into a new home where my bedroom was a spacious renovated attic that had three big skylights—one above my bed, one over a sitting area, and a third above the commode in the ensuite bathroom.

This was the early 1980s and skylights were, to my tween sensibilities, the height of architectural innovation — at least in suburban Connecticut. I spent thousands of hours staring at the sky through those windows, contemplating the universe and my place in it, dreaming of what my life might be like when I was grown, whether I would be able to climb back into my room if I managed to squeeze out through the hinged screen that covered the tilting glass transoms (I could), whether someone flying above our home could look down and see me lying on my twin bed staring into space (they couldn’t.)

I’ve been spending some time lately trolling Zillow and other real estate sites as our family contemplates what might be next for us, and I’ve discovered that I’m still a sucker for a good skylight. For light in general, as longtime readers of these pages will attest.

I can’t remember when I first heard the story about the paralyzed man whose friends carried him on a stretcher to Jesus for healing, and who, when they couldn’t make it through the crowds into the house where the miraculous rabbi was doing his thing, climbed on the roof, hauled their disabled friend up with them, made a hole in the ceiling, and lowered the man down — but it’s long been one of my favorites.

MATTHEW 2 1-5 After a few days, Jesus returned to Capernaum, and word got around that he was back home. A crowd gathered, jamming the entrance so no one could get in or out. He was teaching the Word. They brought a paraplegic to him, carried by four men. When they weren’t able to get in because of the crowd, they removed part of the roof and lowered the paraplegic on his stretcher. Impressed by their bold belief, Jesus said to the paraplegic, “Son, I forgive your sins.”

6-7 Some religion scholars sitting there started whispering among themselves, “He can’t talk that way! That’s blasphemy! God and only God can forgive sins.”

8-12 Jesus knew right away what they were thinking, and said, “Why are you so skeptical? Which is simpler: to say to the paraplegic, ‘I forgive your sins,’ or say, ‘Get up, take your stretcher, and start walking’? Well, just so it’s clear that I’m the Son of Man and authorized to do either, or both . . .” (he looked now at the paraplegic), “Get up. Pick up your stretcher and go home.” And the man did it—got up, grabbed his stretcher, and walked out, with everyone there watching him. They rubbed their eyes, stunned—and then praised God, saying, “We’ve never seen anything like this!”

Whenever that story from the second chapter of the Gospel of St. Mark would come up at church, it would capture my imagination anew, and I would find myself thinking about that man and his friends, roof angles and leverage and ropes and pulleys (with my extremely rudimentary understanding of physics), while gazing through my skylight, examining clouds, looking for stars, or hoping to spot the occasional raptor in flight.

Skylights make me think of my most favorite poet, the late Seamus Heaney, who also was clearly taken with the Gospel story about the paralyzed man lowered through a hole in the roof by his friends to meet Jesus.

Over the course of his life, Heaney, who once told me he was “woefully inarticulate” about his faith (I would beg to differ, motioning to his magnificent oeuvre, but was not going to argue with the great man), wrote three poems that were inspired in some fashion by the man lowered through the roof in search of a miracle or a mercy.

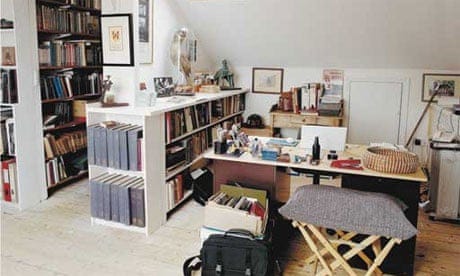

The attic room of the Dublin house where Heaney did much of his writing, also had two skylights.

In fact, one of Heaney’s poems from his 1998 collection Opened Ground that echoes St. Matthew’s story is called, conveniently enough for my purposes here today, “The Skylight.”

"The Skylight"

By Seamus Heaney

You were the one for skylights. I opposed

Cutting into the seasoned tongue-and-groove

Of pitch pine. I liked it low and closed,

Its claustrophobic, nest-up-in-the-roof

Effect. I liked the snuff-dry feeling,

The perfect, trunk-lid fit of the old ceiling.

Under there, it was all hutch and hatch.

The blue slates kept the heat like midnight thatch.

But when the slates came off, extravagant

Sky entered and held surprise wide open.

For days I felt like an inhabitant

Of that house where the man sick of the palsy

Was lowered through the roof, had his sins forgiven,

Was healed, took up his bed and walked away.A second Heaney poem from his final collection, 2010’s Human Chain, expands upon the imagery and narrative of “The Skylight,” in what he called, “Miracle,” read here below by the winsome Wicklow musician Andrew Hozier.

"Miracle"

By Seamus Heaney

Not the one who takes up his bed and walks

But the ones who have known him all along

And carry him in —

Their shoulders numb, the ache and stoop deeplocked

In their backs, the stretcher handles

Slippery with sweat. And no let up

Until he’s strapped on tight, made tiltable

and raised to the tiled roof, then lowered for healing.

Be mindful of them as they stand and wait

For the burn of the paid out ropes to cool,

Their slight lightheadedness and incredulity

To pass, those who had known him all along.And then there is a third Heaney poem, written toward the end of his life in 2013. It was composed in response to a request from his longtime friend, John Deane, founder of Poetry Ireland Review, who asked “of what the personal Christ meant to [him].” The Nobel laureate’s answer came in “The Latecomers,” where he revisits the story of the paralyzed man again, this time from Jesus’ perspective.

"The Latecomers"

By Seamus Heaney

He saw them come, then halt behind the crowd

That wailed and plucked and ringed him, and was glad

They kept their distance. Hedged on every side,

Harried and responsive to their need,

Each hand that stretched, each brief hysteric squeal —

However he assisted and paid heed,

A sudden blank letdown was what he’d feel

Unmanning him when he met the pain of loss

In the eyes of those his reach had failed to bless.

And so he was relieved the newcomers

Had now discovered they’d arrived too late

And gone away. Until he hears them, climbers

On the roof, a sound of tiles being shifted,

The treble scrape of terra cotta lifted

And a paralytic on his pallet

Lowered like a corpse into a grave,

Exhaustion and the imperatives of love

Vied in him. To judge, instruct, reprove,

And ease them body and soul.

Not to abandon but to lay on hands.

Make time. Make whole. Forgive.‘For mercy or miracles’

Last week, on what was the 165th anniversary of the first Marian apparition in Lourdes, France, I watched the startlingly moving documentary Lourdes from French documentary filmmakers Thierry Demaizière and Alban Teurlai.

Filmed in part during the Feast of the Assumption in August 2017, the chiefly vérité Lourdes is set in the southwestern French Pyrenees town of the same name where, beginning on February 11, 1858, a 14-year-old French peasant girl named Bernadette Soubirous claimed to have had visions of the Virgin Mary (“Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception”) at a grotto from which a spring began to flow and has continued to flow for the last 165 years. Soubirous, known as St. Bernadette since Pope Pius XI canonized her in 1933, is said to have had 18 visitations from an apparition of the Virgin Mary between February and July 1858.

From its earliest days, the spring of Our Lady of Lourdes has been believed to contain miraculous healing properties. The Roman Catholic Church has recognized officially 70 miraculous healings since 1858, but countless more miraculous cures have been attributed to its waters and Our Lady. Today, thousands of gallons of waters are pumped from its springs daily where about 350,000 of the approximately 5 million pilgrims who visit Lourdes annually are able to experience full-immersion baths in its piscines.

Even though I spent my earliest years in a devoutly Catholic family, I’ve never held much truck with apparitions. And yet, I’m enough of an aspiring mystic to leave room for the mysterious to occur. Whether the Virgin Mary appeared to St. Bernadette in Lourdes or to anyone else anywhere else is, I suppose, a matter of faith and imagination. As religion journalists, an alleged apparition and/or weeping icon are on our professional bingo cards and in my tenure reporting in Chicago, I covered both: the former in a watermark on an el train underpass and the latter, if memory serves, an Orthodox Christian icon that “wept” holy oil.

I’ve never been to Lourdes and until I saw Lourdes the film, I didn’t have much interest. Now, I want to make a point of visiting, but perhaps not for the most obvious reasons.

For me, the poignancy of the film lies not in miraculous healings — at least not any that were obvious — but in what happens among and between the people who gather at what is arguably the most popular pilgrimage site in the Christian world. Each year tens of thousands of ailing and infirm people flock to Lourdes and are joined by tens of thousands more volunteers from all over the world who help those who need it with everything from transport in specially-adapted buses and trains, eating, bathing, providing medical and emotional comfort, to laughing, flirting, dancing, singing, reading, feeding, ablutions, camaraderie, and spiritual companionship of all kinds.

It’s in this mass of humanity, in kindnesses large and small, in connection and comfort, that, to my eye, the miraculous takes its most obvious and enduring form.

The film follows a number of pilgrims from different walks of life and with differing burdens, beginning with an elderly transgender person from Paris who has been a sex worker for most of their life and has joined a large contingent of other sex workers from the French capital on an annual pilgrimage to Lourdes.

“Protect me,” the unnamed person who left home at the age of 14 and has suffered many years of abuse, prays as the film opens. “I am a man. I am a woman. I’m not sure any more. I’m a bit lost. Enlighten me, Lord. Don’t ever abandon me.”

Later in the film, we watch as the priest who has accompanied the Parisian sex workers to Lourdes asks one of the nuns in charge if the person can fulfill a lifelong dream of serving as an “altar boy” during mass at the grotto. That wish is fulfilled.

There is Patrick, a military veteran who has traveled to Lourdes with his eight-year-old son Jean-Baptiste to pray for his two-year-old son Augustin, who is too ill to make the journey and is at home with is faithful, preternaturally calm, almost beatific mother Laetitia. Jean-Baptiste was born with Prader-Willi syndrome, a condition that affects his thyroid, among other things. While he is the age of an American third grader, because of his condition, he is about the size of an average three- or four-year-old. Augustin was also born with a rare genetic disease — epidermolysis bullosa — a horribly painful condition causing skin to be so fragile it blisters and disintegrates, and, his father explains, has an age expectancy of two. His father asks Our Lady to please intervene and let Augustin stay with them until the following year.

“Don’t forget to pray for all the people who are at Lourdes asking for mercy or miracles,” Laetitia tells darling Jean-Baptiste by cell phone after he reports that he has filled a baby bottle with Lourdes spring water for Augustin to drink when he gets home. (I did a little googling and am pleased to report that both boys, who by my calculations are ages 14 and eight now, were alive and doing well last summer, according to the family’s Facebook page.)

There are so many stories, so many moments that are heartening and brought tears to my eyes not because of anyone’s suffering, though surely that was evident, but because of the massive empathy, kindness, and love on display at every turn.

The story that hit me hardest in the feels was that of Jean, a man about my age with what appeared to be end-stage Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis or ALS.

“At 48, I began to limp, and I found out that I had Lou Gehrig’s disease, which is incurable,” said Jean, who, when the film was shot in 2017, was able still to speak clearly but was otherwise largely paralyzed and used a motorized wheelchair and wore special oxygen mask over his nose. “It’s a disease that slowly buries you alive. Your muscles stop working one by one. Paralysis ultimately sets in, complete paralysis. There is absolutely no hope. Your world falls apart.

“The day I was diagnosed, I was in total shock,” Jean continued, dispassionately. “I could clearly see the terrifying future that awaited me. I was most likely going to die relatively soon. I had a couple of years at most. My head began to spin as I discovered what laid ahead. But this only lasted 10 minutes. An astonishing inner peace came over me and has never left me. I’ve never once felt abandoned. That is what’s kept me going, day after day, and helped me not live in fear.”

Eight years ago this week, my friend Jack lost his battle with the same awful affliction, known as Motor Neuron Disease (rather than ALS or Lou Gehrig’s ) in his native Ireland. The disease took Jack relatively quickly, which I suppose was a certain kind of grace. A decade before we lost Jack, one of my husband’s dearest friends, Joe, succumbed to the disease after several years of suffering brutal declension.

I recall praying for a miracle for Joe and for Jack, not that either of them asked for or expected one. And still, many of us who loved them held out hope — at least for mercy if not a miracle.

In one of the last scenes of Lourdes, Jean visits the healing baths for a full-submersion experience. He is not a small man and there are at least a half dozen attendants (I believe they’re called hospitaliers in French) to help transfer him from his wheelchair, undress him, hoist him carefully from a gurney and lower him gently into the cold spring waters.

Filmed from behind Jean’s head, the audience’s point of view is mostly of the arms and shoulders of the men lifting him into the bath and holding him safely in place, while the healing waters do whatever they might do. Perhaps a miracle. Perhaps mercy. Maybe something of both.

Not to abandon but to lay on hands.

Make time. Make whole. Forgive.

The poolside men assisting Jean at Lourdes are 21st-century iterations of the friends who carried their paralyzed buddy to see Jesus, fought through the crowds, schlepped him up on the roof, lowered him down, and literally held space for him until the miracle-working rabbi forgave his sins, healed his body, and told him to pick up his stretcher and go home.

Do miracles happen? I believe so, yes.

Are miracles always what we expect them to be? No.

Can we be miraculous for each other by embodying lovingkindness, compassion, tenderness and mercy? Absolutely.

Any place that can make millions of people who feel abandoned, outcast, forgotten, marginalized, disposable, and hopeless feel that they belong, are precious, valued, sacred, beloved, whole, enough, and not alone in the brokenness we all share as humans is surely a holy place where God is busy. And I want to see it for myself.

One of these days, Lord willing, perhaps I’ll make it to Lourdes as a hospitaliere.

There are loads of ways to volunteer, but here’s the main volunteer portal at the official Lourdes site: https://www.lourdes-france.com/en/benevole/

BITS AND BOBS, ODDS AND ENDS

This week I had the great pleasure of joining my friend Sarah Heath and new friend Justin Gentry on their REVcovery podcast. It was a super fun, truly deep conversation where we discussed vocation (of all sorts) after evangelicalism and/or deconstruction, spirituality, church, #religionjournalism, #mysticism, beloved teacher/mentor Richard Rohr, #journalism, #midlife, #fallingupward, #bungee jumping, leaps of faith, not living from a place of fear, facing/integrating/overcoming fear, and embracing what we don't know, and how to be a non-anxious presence in a terribly anxious world.

I’ve done a lot of podcast episodes (including many where I was the co-host) and this is one of my favorites. Tune in HERE or wherever you get your podcasts.

PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER

As I type these words, reports are that President Jimmy Carter, with 98 years of life, has entered hospice at home and is likely standing close to the threshold between this world and what comes next.

Jimmy Carter is the first president whose election I remember. My father was a fan of the peanut farmer from Georgia while he was in office and ever more so after he left. As was I. In fact, the older I get, the more I appreciate President Carter’s witness, his long obedience in the same direction, if you will.

As a journalist, I had the opportunity to interview him once, by phone, back in 2009 when I was still writing for the Chicago Sun-Times. I recall being struck by his plainspokenness. Mr. Rogers he was not. He was tough, smart, astute, and kind, but not saccharine. I’m grateful for our lives having momentarily intersected. (You can read the Q & A of our conversation — when he was a spry 85 — HERE.)

Please join me in lifting him up, his beloved Rosalynn, his children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, family, friends, and collaborators who know and love him most. May dear Jimmy have all that he needs most right now, the peace that passes all understanding, joy at a life well-lived, no fear, and a grace-filled transition.

He is a magnificent human, a model for all of us. And those who claim to be followers of Jesus the Christ would do well to take a long look at President Carter’s life and emulate it.

As we each head into a new week, let us do our very best to be as brave and kind as we can be.

Remember that you haven’t met yet everyone you will love and you haven’t met yet everyone who will love you.

Much love from me,

As always with your writing, I felt like a kid rooting around in a treasure chest. I also listened to the podcast. It was great to learn some things about you that I didn't already know. Funny enough, even though I knew the story about you bungee jumping off the bridge, and have seen the video, as you told it my hands started sweating and my pulse quickened.

Beautiful. Did not expect to cry in my coffee, but it was a good kind of cry. Thank you.